Fourth of 4 parts

Now that I have presented my reasons for supporting the American paradigm on which the Philippines can model, in full or in part, its federal form (namely, a limited, federal, presidential government), I will henceforth present a few key features and safeguards of the U.S. government which I propose be assimilated into the new Philippine constitution. However, it must be noted that, albeit the Philippine government was partially modeled after the American government, these key features were excluded from being incorporated into the Philippine constitution.

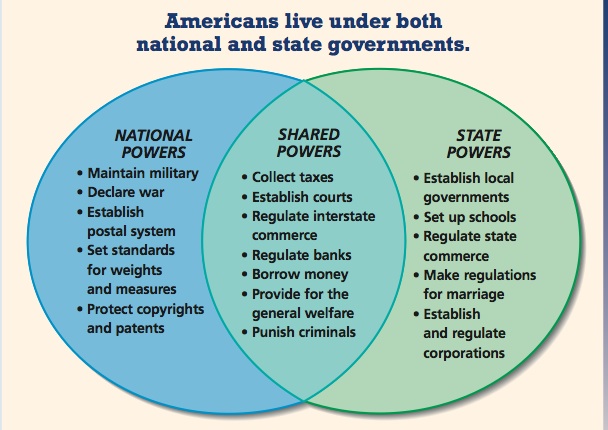

Such safeguards are not only what starkly differentiate the U.S. government from the Philippine government, but they are precisely what account for the general effectiveness of the former’s system of checks and balances---namely, a federalist system by which power is equally divided by a central government and the states, an electoral college to elect the president, a Senate with its members elected by their districts rather than at large, and recourse for the states whenever their sovereignty is threatened by a tyrannical federal government. Due to much of the public’s oblivion to these distinctions, I have elucidated them in my commentary entitled “Is the Philippine Government an American Replica?”

Senate

First, I propose the restructuring of the Philippine Senate pursuant to the American model of equal regional representation, whereby each region or state will elect two senators. Indeed, this is a drastic deviation of the current method of the populace voting for twenty-four senators nationwide or at large. Not only would this arrangement be congenial to the unique situation of each region or state, it would empower the small states as well. Indeed, as American founder William Davie stated, “The protection of the small states against the ambition and influence of the larger members, could only be effected by arming them with an equal power in one branch of the legislature.” Hence, equal representation in the Senate is a safeguard against what American founder James Madison called “the tyranny of the majority.”

Since the lower chamber of Congress known as the House of Representatives is composed of members elected directly by the people, it has been characterized as embodying the unfettered “passions” of the people. By contrast, members of the upper house known as the Senate shall be elected or appointed by the regional or state legislatures, whose members are inclined to be refined and informed. That is why Madison wrote, “The use of the Senate is to consist in its proceedings with more coolness, with more system and with more wisdom, than the popular branch.” Put more simply by American founder George Washington, the scalding heat of the “tea” of the House is placed into the “senatorial saucer to cool it.”

Additionally, the election or appointment of senators by regional or state legislatures will decrease the influence of special interest groups on senatoriables, since they often fund costly state-wide races. Political commentator John DeMaggio elaborates:

Senators would no longer be bound by allegiances to these special interests. Candidates would not be obliged to receive funding from political parties for their nonexistent campaign limiting a Senator’s obligation to the national political party. Senators would be more obligated to serve the interests of their State . . . rather than a national political party or special interests.

Hence, the republican nature of the Senate serves as a check and balance on the democratic nature of the House, a distinct feature of American federalism, which ultimately keeps an overreaching federal government at bay.

Electoral College

Second, I propose the establishment of an electoral college (EC) to elect the president as opposed to the current form of direct or popular election. Being comprised of what American founder John Jay characterizes as “the most enlightened and respectable citizens. . . their votes will be directed to those men only who have become the most distinguished by their abilities and virtue. . . As an assembly of select electors possess. . . the means of extensive and accurate information relative to men and characters, so will their appointments bear at least equal marks of discretion and discernment . . .”

By contrast, the current presidential electoral system via popular vote is often dominated by man’s raw passion and impulse (as in the House) because as American founder Elbridge Gerry stressed, the “people are uninformed, and would be misled by a few designing men.” Perhaps that accounts for the banal election of incompetent politicians, unfavorable dynasties, and inexperienced celebrities in the Philippines. Hence, the EC, much as the Senate, serves as a check and safeguard against the populace’s unfettered passion and impulsive drive.

The EC also serves to ensure fair representation for the small and least populated regions or states just as it does in the U.S. Senate. Consider that of the seventeen regions, the two most populous ones are Southern Tagalog (Region IV) at 14,414,774 and the National Capital Region (Region XIII) at 12,877,253. Naturally, a direct election of the president would be largely in their favor to the detriment of the less populous regions, such as the Cordillera (Region XIV) at 1,722,006 or Caraga (Region XVI) at 2,596,709.

That is why I propose, in addition to the equivalent number of House members, two representatives be elected or appointed by each region or state in order to constitute a Philippine electoral college (EC) similar to the U.S., whereby each region will be equally represented, regardless of its size. In so doing, the president will be the president of the whole Philippines, not just of the largest regions or metropolitan areas.

The final purpose of the EC is to facilitate the preclusion of voter fraud. However, in order for this to be effective, the presidential electoral system must become decentralized. Just as in the U.S., each individual state legislates its own election laws, each Philippine region or state must do likewise. In so doing, corrupt federal election officials would find it virtually impossible to fix or “rig” the presidential election due to the electoral autonomy of every region or state and the functioning of local election judges, tasked with multiple responsibilities.

Even when anomalies are discovered after the voting results, they can easily be isolated to one or only a few regions or states, which would make for speedy recounts, as was the case in the 2000 U.S. presidential election wherein a voting dispute occurred between George W. Bush and Al Gore in Florida for only a few weeks. Contrast that with the dispute between Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos and Leni Robredo which has persisted for over two years. Consider also how cost-effective the electoral process would be due to decentralization and curtailing of lawsuits.

The electors shall not hold public office in any branch of the federal government, be given a salary, or have tenure, and whereupon its sole function of electing the president and vice-president is executed, the EC shall immediately be dissolved. Hence, they will be insulated from national political pressure. Such a temporary function certainly addresses American founder Alexander Hamilton’s concern that presidential selection should not “depend on any preexisting bodies of men who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes.” The manner by which electors are selected shall be at the sole discretion of each individual state or region---e.g., via a state or region’s legislature, via a state or region’s governor on the authority of that state or region’s legislature.

It is ostensible that the EC has a positive impact and wide implications on governance. Such a significant feature, with all its safeguards, is the cornerstone of American federalism, of which the Philippine government is bereft. Indeed, the EC is also an alternative to a direct democracy (as is currently the case), authoritarianism, and parliamentary government.

Nullification

Third, America’s founders brilliantly concocted two checks as a remedy for the states to counter an overreaching or tyrannical national government. The remedies are state nullification of unconstitutional federal laws and an Article V Convention of States (COS). The former is, according to Jefferson, “the rightful remedy” against “all unauthorized acts done” by the national government and was executed effectively in defiance of a federal embargo, the Alien and Sedition Acts, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In my commentary entitled The Peak of Tyranny and End of Its Destruction, I cited two more recent examples in which Montana, Alabama, and Wyoming amended their state constitutions, nullifying Obamacare.

In defiance to President Barack Obama’s executive orders to banning certain types of firearms, several governors, state legislators, and sheriffs have taken measures to quell or nullify any presidential decree, which did not conform to their own state’s gun regulations. Some legislators have gone so far as to prepare legislation which would criminalize any attempt of federal agents to enforce the new federal gun ownership restrictions. One sheriff in Oregon (Tim Mueller) even wrote a letter to Vice President Joe Biden in which he declared that neither he nor his deputies would enforce any federal gun law, which he deems unconstitutional. Among the states which exercised such recalcitrant acts were Mississippi, Kentucky, Oregon, Minnesota, Alabama, Tennessee, Wyoming, Utah, Alaska, Florida, and Texas.

Convention of States

In Federalist 85, Hamilton alludes to the second remedy when he says, “. . . we may safely rely on the disposition of the state legislatures to erect barriers against the encroachments of the national authority.” He is referring to assembling a Convention of States (COS), which is actually embodied in Article V of the U.S. Constitution:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress ….

Put plainly and simply, thirty-four states of the U.S. must consent to deliberation in a convention of states (not a constitutional convention, which would be a formidable option) to propose constitutional amendments. Thirty-eight states must ratify the amendments in order for them to become binding and effective. In this way, the states can put the national government in check regardless of who occupies the presidency, Congress, or the Supreme Court. As of this writing, twelve states have passed a COS resolution. Furthermore, the aforementioned remedies as state nullification and an Article V COS are essential in lawfully preserving federalism, while precluding “mob rule.”

In the Philippine context, a clause pertinent to regional or state nullification of intrusive federal laws can and should be annexed to the draft constitution in order to preclude jurisdictional discrepancies, wherein both the regions and national government purport to defend and uphold the Constitution. Unfortunately, such a clause is nonexistent in the U.S. Constitution, which has been the cause for the aforementioned discrepancies and can thus serve as an example of unintended consequences from which the Philippines can learn. In terms of annexing a COS clause to the draft constitution, the number of regions needed for deliberation and ratification will be smaller than our U.S. counterpart, since the number of regions created and established via federalism will be significantly smaller than the fifty states of the U.S. (e.g., eleven pursuant to LDP Institute’s model and eighteen pursuant to RBH 8).

Furthermore, a Senate elected by the regions or states, an electoral college to elect the President, and recourse for the regions or states against an overreaching federal government are checks and balances safeguarding the sovereignty of the regions or states and the people. They are elements, which, in spite of their historical significance to American federalism, have never been assimilated into Philippine government. Perhaps now is the time in the clamor for federalism and as an alternative to a costly and more drastic shift to a federal parliamentary system.

However, in spite of the ostensible advantages of my federalist proposal, it must be noted that it is not a “magic bullet” or the single, perfect solution to everything ailing the Philippines. Rather it is a remedy to address certain issues, which, in order to have maximum positive impact, must be executed in concert with other measures, e.g., the enforcement of current laws, economic liberalization to curb protectionist policies and attract direct foreign investments, and cultural changes in order to cultivate an informed, disciplined, industrious, and active citizenry which will strengthen preexisting, fundamental, social institutions. The latter is imperative, lest the electorate continues to elect incompetent or corrupt politicians, and that will occur under any system of governance—unitary or federal, presidential or parliamentary.

This is excerpted from “The Philippine Case for Federalism, Its Form, and Its Safeguards” by Marcial Bonifacio. Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 are accessible by clicking on their links.

Third of 4 parts

Having presented my reasons for the federalist shift while also addressing contrarian views, I also propose that the Constitutional Commission scrutinizes, adapts, and includes the American government’s model---in full or, at least, in part. If only in part, I propose a few particular safeguards be assimilated into the new Philippine constitution. In the meantime, it seems appropriate to scrutinize my reasons for including the U.S. model in making the transition to federalism.

Best Ideas

First and foremost, America’s republic is comprised of the best historical ideas. Indeed, the founders scrutinized the governing systems of the predominant Western civilizations---ancient and contemporary. These include Greece, Rome, France, and England from which the founders derived the concepts of liberty, justice, trial by jury, separation of powers, democracy, republicanism, and self-government. The founders meticulously studied the rise and fall of tyrannical governments in those nations, as well as their own experience with King George III in framing a constitution which would preclude such occurrences in the U.S.

Preexisting Government Infrastructure

Second, since the Philippine government was largely framed after the U.S. government, the familiar preexisting federal infrastructure or apparatus of the separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches facilitates a more congenial transition to federalism much more so than abolishing it as parliamentary government advocates and proponents of PDP-Laban Federalism Institute’s model seek to do. Even the anti-colonialist Delegate Manuel Roxas defended the ratification of the 1935 Constitution (although it is a gross variation of America’s original constitution):

Why have we preferred the Government established under this draft? Because it is the Government with which we are familiar. It is the form of government fundamentally such as it exists today; it is the only kind of government we have found to be in consonance with our experience, and with the necessary modification capable of permitting a fair play of social forces and allowing the people to conduct the presidential system.

It must be noted that I do not oppose a parliamentary form of government per se. I simply would support it only as a last resort, i.e., when all reforms under a presidential federal system (e.g., the establishment of an electoral college to elect the president and a Senate elected by regional legislatures instead of at large) fail, but I digress.

Resiliency

Third, America’s system has proven to be the most resilient. Constitutional law Professor Hugh Hewitt points out:

The work of collective genius that is the Constitution has been tested by everything from an actual civil war that claimed 600,000 lives to various panics, two world wars, the Great Depression, and the Great Recession, not to mention impeachments and assassinations, political-judicial meltdowns like Florida in 2000, and dozens of scandals---and it does not break. It is more resilient than any other modern constitution, a remarkable, nearly perfect balance of competing powers and separated authorities that has endured and will endure. Those who fear it is off the road and in the ditch have to ignore history’s many examples of America righting itself after trauma and setback.

Consider America’s progress in the abolition of slavery, suffrage for women, and civil rights for blacks, all of which happened within 229 years of the establishment of the U.S. government. In spite of such turbulent occasions, the world’s oldest written supreme law of the land, the U.S. Constitution, remains largely intact. Contrast that with our three Philippine constitutions---of 1935, 1973, and 1987---all promulgated and implemented within a single century. Additionally, President Rodrigo Duterte has raised the specter of a revolutionary government, which all betokens the instability of the Philippine government.

Unequivocal Language

Fourth, the language of the U.S. Constitution is very clear in distinguishing the powers of the federal government from that of the states. Article 1, Section 8 enumerates the federal powers:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States…To borrow Money on the credit of the United States…To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes…To coin money…To establish Post Offices and post Roads…To raise and support Armies.

The Tenth Amendment, the last of the Bill of Rights, betokens the threshold at which the states (or the people) are sovereign, which is the cornerstone of federalism. It states: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the People.” The American founder and principal author of the Constitution, James Madison, elaborates on the nature of these powers in Federalist 45:

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the Federal Government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State Governments are numerous and indefinite. The former will be exercised principally on external objects, as war, peace negotiation, and foreign commerce . . . The powers reserved to the several states will extend to all the objects, which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the state.

Indeed, it is those “few and defined” powers of the federal government which accounts for a simple, comprehensible, and short constitution. Contrast that with our lengthy constitution of 1987, which manifests a government exceeding the size and scope imposed by America’s founders.

Based on Natural Rights

Fifth, it is the first written constitution based on our timeless, ubiquitous, natural rights, which intrinsically circumscribe the national government and betoken the vast range of our individual liberty. Indeed, the U.S. Declaration of Independence (upon which America’s constitution is based) betokens man’s universal and intrinsic equality and endowment of “certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Even the Philippine revolutionary and anti-colonialist Apolinario Mabini acknowledged such rights, stemming from “natural law,” when attributing the success of the U.S. government to the major work of two of its founders, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine:

The ruler’s success is always to be found in the adjustment of his practical measures to the natural and immutable order of things and to the special needs of the locality, an adjustment that can be made with the help of theoretical knowledge and experience. The source of all failures in government can therefore be found, not in (mistaken) theories but in unprincipled practices arising from base passions or ignorance. If the Government of the United States has been able to lead the Union along the paths of prosperity and greatness, it is because its practices have not diverged from the theories contained in the Declaration of Independence and of the Rights of Man, which constitute an exposition of the principles of natural law implanted by the scientific revolutions in the political field.

This is excerpted from “The Philippine Case for Federalism, Its Form, and Its Safeguards” by Marcial Bonifacio. Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 are accessible by clicking on their links.

By Marcial Bonifacio

Second of 4 parts

Apart from the ostensible advantages of federalism, critics persist in their tenacity. Their recalcitrance dissuades others from supporting or even learning more about federalism, hence perpetuating the status quo. That is why I have addressed some of their criticisms below.

Economy May ‘Go to Hell’

Critics commonly point to the findings of DOF Secretary Carlos Dominguez III who stated that the national government may incur a 6.7% deficit, interest rates would rise by up to 6%, 95% of national government employees may be laid off, and the country’s investment-grade credit ratings may “go to hell.” ConCom technical working head Wendell Tamayo estimates the cost of establishing 16 federated regions, Bangsamoro and Cordillera regions, four federal courts, and six constitutional commissions at P2.2 trillion, while Rosario Manasan of the Philippine Institute of Development Studies estimates that approximately P55 billion per year will need to be appropriated for the salaries of new federal state elected officials.

Some economists like Victor Abola (professor of the University of Asia and the Pacific) point to a few federal countries which are imperiled by hyperinflation and fear that a federal Philippines may be subjected to the same aftermath. Due to Venezuela’s current inflation rate of 25%, things cost 250 times more today than a year ago. Other federal countries like Mexico and Brazil have a similar result due to their localities’ reckless spending on elections, which Abola states is “the primary reason for their hyperinflation episodes . . . which exceeded 4,000% inflation.”

In spite of such negative financial analysis, there are potential measures which could preclude or mitigate some of the aforementioned effects. For example, ConCom spokesman Ding Generoso has proposed the appropriations for implementing federalism emanate from one of several sources: regional taxes/fees, share of top revenue sources, share of equalization fund, the General Appropriations Act, or natural resources income. Political scientist Antonio Contreras suggests that some of federalism’s additional costs can be compensated for by the lower costs of transactions, travel, and communication due to decentralization.

Another source would emanate from an expanded tax base due to increased domestic and foreign investments. In order to be competitive, the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) suggests the corporate income tax (CIT) be lowered from 30% to 20%. Although the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion 2 (TRAIN 2) law will lower the CIT to 25%, the average rate of the Philippines’ Southeast Asian neighbors is 22.7%. Hence, a more competitive CIT would attract more investors and create more jobs which, in turn, would translate into more tax revenue.

Also, fiscal incentives for foreign investors in economic zones should be maintained. For example, the Bases Conversion and Development Act of 1992 grants free port locators a 5% tax on gross income earned. Unfortunately, TRAIN 2 will repeal such incentives, which the AmCham claimed would “lead to an end to expansions by many foreign investors and a reversal of the success in recent decades in attracting thousands of foreign firms to invest in the country.”

Indeed, this concern is shared by Subic Bay Freeport Chamber of Commerce President Danny Piano who fears the prospect of “capital flight” and Charito Plaza, director general of the Philippine Export Zone Authority, who will continue to defend the fiscal incentives. Aside from retaining the 5% tax, the financial giant HSBC suggests loosening foreign ownership restrictions via charter change, which would increase the Philippines’ share (currently the lowest) in ASEAN’s “FDI windfall.”

Additionally, all business tax cuts and fiscal incentives should be made permanent, as well as repealing the protectionist clause of the 1987 Constitution in order to boost long-term commitments by investors. Indeed, such “productive investment,” stated UP professor Maria Bautista, “will generate future streams of income that will not only increase domestic output and income, but also allow the country to service its debt.” Perhaps the anticipated 95% of laid off national government employees can be reabsorbed into the revitalized private economy or continue their public service on a local level. Either way, different economic opportunities will abound due to the reallocation of capital precipitated by tax reform and economic liberalization.

ConCom Atty. Rodolfo Robles points out that the national budget is approximately P3.75 trillion and that 40% of it is illegally misdirected. “Sa simple arithmetic po,” stated Robles, “ayan ay 1.5 trillion, ang napupunta sa graft and corruption.” He continued to say that at least half of it can be retrieved with a sufficient supply of attorneys.

Recently, in the U.S., Sen. Rand Paul and Rep. Mark Sanford introduced the “Penny Plan” or the “One Percent Solution.” It mandates Congress to reduce federal spending in all departments by one cent on the dollar. This would drastically curtail inefficiencies from wasteful spending and balance the budget over a period of five years. Surely, the Philippines can adapt such a plan in order to cap or mitigate the anticipated deficit as a result of instituting federalism. Call it the “Centabo Plan.”

I would add that with the regions assuming more fiduciary responsibility, the people will be able to retain more of their hard-earned income, while their region more effectively delivers services otherwise performed by the national government. Such an arrangement would also allocate resources more efficiently and fairly, since taxpayers residing in Manila would no longer have to fund the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) or condoms for lazy, mendicant perverts residing in Zamboanga City (presuming 4Ps and the RH Law get repealed, or the regions have the option to nullify them by virtue of federalism, just as the U.S. is currently in the process of repealing the unconstitutional Affordable Care Act, putatively “Obamacare”). Indeed, such decentralization echoes ConCom member Dr. Julio Teehankee’s sentiment that “the proposed draft federal constitution encourages the national government to go on a diet and the regions to go on a muscle-building regimen.”

In terms of hyperinflation, it is highly misleading and even disingenuous to attribute it to federalism per se. Indeed, Venezuela’s centralized federalism (an oxymoron) is simply a euphemism for its federalized socialism, whose perpetual budget deficits and inability to borrow money, has resorted to excessive printing of increasingly devalued money. Consequently, hyperinflation has become pervasive. In the case of Brazil and Mexico, it is ostensibly due to poor management and or flawed public policy in election campaign financing which has led to such high inflation rates. That could be remedied by transparency legislation or strict penalties for exceeding a fixed limit on campaign financing or outright privatization of campaign financing. Ergo, hyperinflation need not be attributable to federalism.

Comparing the Philippines to the U.S. and Germany an Apples to Oranges Comparison

Some opponents assert that presenting the economic success of advanced, western, federal countries like the U.S. and Germany is disingenuous, since the Philippines is generally still a developing, Asian country---an apples to oranges comparison. However, the eastern, federal states of India and Malaysia more closely resemble the Philippines and have a relatively stable government and growing economy. Malaysia’s economic growth is at 5% with a GDP of $863.3 billion and foreign direct investment (FDI) at $9.9 billion. India, whose history is also influenced by colonialism and the English language, has a growth rate of 7.3% with a GDP of $8.7 trillion and FDI at $4.5 billion. Compare those economic indicators to that of the Philippines with a 5.8% growth rate, a GDP of $805.2 billion, and FDI at $7.9 billion.

Increased Power to Local Dynasties and Oligarchs

Apart from the ostensible advantages, some are fearful that federalism will enable political dynasties to dominate the regions. However, a vigilant and informed citizenry can prevent such occurrences or take counter measures after the fact, such as passing and enforcing anti-dynasty and transparency laws as Senator Nene Pimentel suggests. However, as I wrote in my commentary entitled Why Manny Pacquiao’s Defeat Could Be a Win for the Country, “I do not oppose dynasties, insofar as their members are fairly and democratically elected and serve the interests of their constituents. However, when they are self-serving or hold power only for namesake, I oppose them and any office holder—dynasty clan or not.”

Anyway, should all remedies fail, citizens and businesses can simply migrate to another region, which is more congenial to their own interests, values, economic preferences, or lifestyle. Over whom would the dynastic oligarchs rule and depend on for tax revenue, if everyone migrated elsewhere? Would they then not be compelled to compete with other regions by providing quality government services, e.g., infrastructure, public safety, property rights protection, and contract enforcement?

Federalism Too New and Foreign to the Philippines

Some opponents stress that since federalism is a foreign concept or that the Philippines lacks historical experience in regional autonomy (in contrast to the U.S., Malaysia, and Germany), such a system would be inappropriate or not viable. However, I contend that El Filibusterismo, a sewer system, jeepneys, smart phones, and a Red Cross did not always exist, and, indeed, did change Philippine life for the better. Hence, should we have opted to never have introduced them as well? A prosperous nation demands openness to positive change, and education can accommodate any kind of change, despite its drastic implications.

Anyway, as Chief Justice Artemio Panganiban points out, “The idea of federalism is not really new to us. Salvador Araneta, a delegate to the 1971 Constitutional Convention (ConCon), proposed it in his ‘Bayanikasan Constitution.’ Jose Abueva, the secretary of the same ConCon, has written several papers detailing his version of federalism.” Even as early as 1900, an Ilocano intellectual named Isabelo de los Reyes, envisioned a federal constitution with seven states comprising the Philippines.

A Sufficient Government Local Code

In terms of regional autonomy, critics point out that the Government Local Code renders federalism obsolete, since the Code is intended to devolve power and disburse internal revenue allotments (IRAs) to localities. “And yet,” stated Panganiban, “these do not seem to be enough because our Constitution mandates one national police to which the local police are legally beholden, and the Department of Budget and Management which could withhold IRAs.” Such local autonomy “with strings attached” makes them prone to corruption, or, at least, apathetically unresponsive to the demands of their populace. Federalism will cut those strings and enable the regions or states to determine their own future.

Neglected Poor Regions

Naysayers of federalism also raise the issue of impoverished regions worsening due to reduced national support. However, I contend that such dependency or mendicancy is precisely what has retarded their capacity to cultivate their own resources in order to produce prosperity. It is conventional economic wisdom that prosperous economies consist of most, if not all, of the following key variables: few or no entry barriers to trade, an educated labor force, natural resources, adherence to the rule of law, sustainable infrastructure, and high-scale technology. Those variables can be cultivated by an efficient, corrupt-free government, quality educational institutions, economic liberalization, and pro-growth tax policy.

Recent history is certainly instructive in providing the proper perspective. Consider the economic development and growth in post-World War II Japan after the atomic bomb converted its cities into ruins, yet the nation is currently the world’s third largest economy. Within our own borders, after the recall of American naval bases in Subic Bay and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 (wherein the territory was reduced to an ash heap), it was shortly transformed and lauded by various world leaders as a successful trade port and a paragon for economic growth. I elaborate on Subic in my commentary entitled Why the Senate Needs More Dick. If Japan and Subic can prosper, under such overwhelming odds, why not any other region or state in the Philippines?

Perhaps special concessions can be made to the more disadvantaged regions like Mindanao, which should be targeted and temporary as an incentive to be self-sufficient. Indeed, I would not be averse to Chief Justice Reynato Puno’s concept of “evolving federalism” by which the lesser developed regions remain in the status of “autonomous regions” until they are capable of graduating to the status of “full states.” In that case, benchmarks should be established instead of a timeline.

This is excerpted from “The Philippine Case for Federalism, Its Form, and Its Safeguards” by Marcial Bonifacio. Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 are accessible by clicking on their links.

By Marcial Bonifacio

First of 4 parts

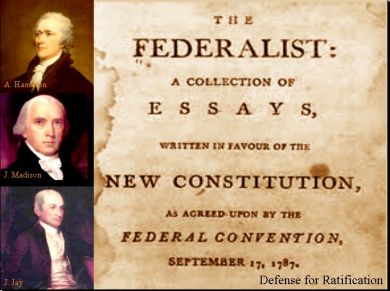

In this proposal, I have frequently cited America’s founders, since federalism (as a systematic study of governance wherein power is shared between a central government and state governments) is often attributable to them, and their intent is made manifest in a collection of their 1787 constitutional convention debates published in The Federalist. “On every question of construction,” states the American founder Thomas Jefferson, “carry ourselves back to the time when the Constitution was adopted, recollect the spirit manifested in the debates and instead of trying what meaning may be squeezed out of the text, or invented against it, conform to the probable one in which it was passed.”

Vertical Balance of Power

First and foremost, a federalist system would divide power between the national government and state or regional governments wherein such a dispersal of power would create a vertical, as well as horizontal balance of power. The American founding father Alexander Hamilton elaborates:

This balance between the National and State governments ought to be dwelt on with peculiar attention, as it is of the utmost importance. It forms a double security to the people. If one encroaches on their rights they will find a powerful protection in the other. Indeed, they will both be prevented from overpassing their constitutional limits by a certain rivalship, which will ever subsist between them.

Close Proximity of States to the People

Second, state autonomy enables each state to govern more effectively due to their close proximity to the people residing in those states. Jefferson wrote about the U.S., “Were not this great country already divided into states, that division must be made, that each might do for itself what concerns itself directly, and what it can so much better do than a distant authority.” After all, do not our local public servants have a more accurate perspective of affairs within their own jurisdiction than those governing from Malacanang Palace?

Even President Rodrigo Duterte miscalculated the duration of his war on drugs, originally insisting on a 6-month purging operation, which he now says will require one more full year. Such a reassessment is apparently due to his newly acquired national perspective and experience, as opposed to his provincial perspective and experience from being Davao City mayor for 22 years. Although federalism will benefit the people in general, according to Consultative Committee (ConCom) member Eddie Alih, it will be especially expedient to “the lost and the least because shifting to a federal setup will bring government social services closer to the poor.”

Accommodation for a Vastly Diverse Populace

Third, state autonomy more easily accommodates governance of a nation comprised of more than 7,000 islands, several religious groups, and more than a hundred ethno-linguistic groups. The conquests of Spain and Japan and the American occupation have also had a cultural influence on the indigenous people, as well as trade with the Chinese, Arabs, and Malays. Naturally such diversity entails differing interests, modes of production, and social-ethnic concerns, all of which may require differing regulations or laws designed for the unique circumstances of each state or region.

Now consider some actual examples of federalism taking effect in America, which betoken unique variations in law, taxation, economics, religion, individual liberty, and culture. The state of Utah is heavily populated by Mormons, while the mountainous state of Tennessee and Alabama are pervaded by evangelical Christians. Recreational marijuana is legal in California wherein same-sex marriage and a large Filipino populace co-exist.

Massachusetts has mandatory health insurance and permits open carry of a firearm. New York has the highest taxes, the most stringent gun control laws, business regulations, and the highest rate of fetal abortions. (Perhaps those are the “New York values” to which Senator Ted Cruz was referring in his 2016 presidential primary run against Donald Trump.)

Florida and Texas have the lowest income tax rates, no mandatory state income tax, and they happen to be the most favorable states for bass fishermen due to their numerous lakes, rivers, and streams. Philadelphia, the birthplace of America’s constitution, levies a sugary drink or “soda tax.” For advocates of capital punishment, the options are varied---electrocution in Kentucky, gas inhalation in Arizona, firing squad in Utah, and hanging or lethal injection in Washington.

Cannot our countrymen relate to such varying factors? Consider similar issues of which some are controversial as well as divisive but could easily be addressed by the states or regions---the drug war, the Mindanao conflict, RH Law, the death penalty, marriage dissolution, same-sex marriage recognition and benefits, jeepney fare hikes, VAT, etc. In terms of core competencies or comparative advantages, Cebu is the exclusive producer of dolomite and graywacke, while Capiz and Ilocos Norte exclusively produce cotton. Palawan and Boracay are the top tourist destinations of the Philippines, due to their beaches and the latter’s party ambience.

Furthermore, possessing regional or state sovereignty under federalism, allows each state or region to address such issues pursuant to their unique geographical or demographical situation. “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system,” contends American Chief Justice Louis Brandeis, “that a single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.” Indeed, impoverished regions can learn from and mimic affluent regions by scrutinizing their economy, tax system, business regulations, and commerce practices, while education administrators in one region can do likewise with successful schools in other regions. In turn, such competitive regions could eventually decongest Manila.

Such a diversity would naturally appeal to the marginalized or disaffected members of society (e.g., the New People’s Army, Abu Sayyaf, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap, the Lumads, and Cordillera). While there is much controversy over the constitutionality of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), the establishment of a Bangsamoro state or region (to replace the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao) via federalism would render the BBL and Bangsamoro Organic Law obsolete, since all states or regions would be equally autonomous simultaneously, at least eventually.

This is excerpted from “The Philippine Case for Federalism, Its Form, and Its Safeguards” by Marcial Bonifacio. Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 are accessible by clicking on their links.